Future Predictions: Hunger, Poverty, and Climate Change

By Mahjobeh Badakhsh, Program Coordinator

Poverty and the Rising Costs of Living

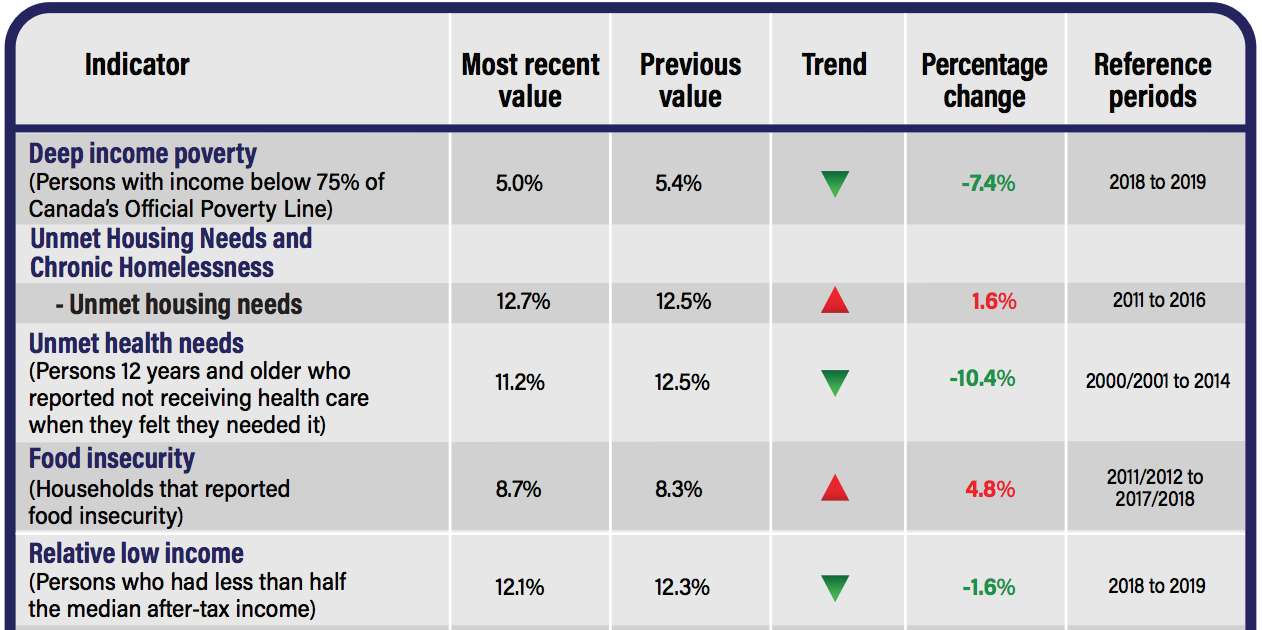

Across Canada, increased costs of living, such as housing, gas prices, and food prices have drastically outpaced increases in wages. As a result, 11% of the overall Canadian population and 20% of Vancouverites live below the national poverty line. People that live in poverty are often unable to pay for food, housing, childcare, health care, and education. The good news is that poverty rates are trending downwards. The bad news is that despite the downward trend, other poverty indicators, including food insecurity and unmet housing needs, suggest increased adversity for marginalized groups living in low-income households. Canadians are having to choose between essential needs, such as paying rent or buying groceries.

A recent poll conducted by Grassroots Public Affairs, in collaboration with Food Banks Canada, reveals how things have changed since last year. While household debt and rising unemployment were viewed as the largest obstacle to food affordability in 2020, 46% of Canadians today consider the costs of housing to be the biggest barrier to food affordability. Even more concerning, housing needs and chronic homelessness, currently at 12.7%, are expected to continually increase.

From Dalhousie University Faculty of Agriculture

Rising Grocery Costs and Food Insecurity

Canada has one of the safest food systems in the world, but the most recent Food Price Report forecasts an overall food price increase of up to 5% in 2021, meaning the annual food expenditure could increase by as much as $695 compared to previous years. As seen in the graph on the right, the most significant price increase is predicted for meat, vegetables, and bakery.

New COVID-19 safety protocols and preventative measures in the agri-food supply are largely responsible for higher grocery prices. The continued impact of COVID-19, the loss of the food manufacturing sector, the growth in e-commerce and online services, and the effects of climate change are key food price factors to look out for in the next few years. According to Stats Canada, 1 in 7 Canadians experiences food insecurity. This is up from pre-pandemic levels and with rising food and housing costs, we can expect to see an even greater increase in food insecurity levels.

Guaranteed Basic Income

The pandemic has also recharged a collective discussion about a guaranteed basic income. Wages continue to fall behind the rapidly rising costs of living, signaling a global outcry and an increase in advocacy for a living wage. In British Columbia, the minimum wage was recently increased to $15.20 per hour, while a $15 per hour minimum wage was approved at the federal level. Earlier this year, the Liberal Party of Canada also adopted a universal basic income (UBI) resolution to assist low-income Canadians and seniors achieve an adequate standard of living.

However, a universal basic income for all may not be the best option when tackling poverty in B.C. A recent report by an expert panel of economists, Covering All the Basics: Reforms for A More Just Society, found that in order to create a more just society and eradicate poverty, governments should prioritize expansive reforms to existing social support programs for vulnerable groups. A more targeted approach to helping disadvantaged populations, rather than a UBI, is needed to lift people out of poverty.

Inequitable wealth distribution and systemic injustice cannot be ignored when talking about food insecurity and poverty reduction. Marginalized groups often bear the disproportionate burden of poverty: they are at higher risk of experiencing multidimensional poverty and continue to come up against barriers in accessing support. According to 2016 census data, the national poverty rate for racialized individuals was nearly double (20.6%) that of non-racialized Canadians. The highest food insecurity rate is also experienced by black (28.9%) and Indigenous (28.2%) peoples. However, not enough high-quality data is available to guide the development of appropriate poverty reduction efforts and policies to achieve an equitable distribution of wealth.

Poverty, Food Insecurity and Climate Change

Without immediate efforts to adapt to climate change, poverty and food insecurity will continue to increase substantially. According to the United Nations’ Emissions Gap Report, global temperatures are on track to increase by 3.2 degrees Celsius this century, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are also projected to increase over the next decade, even when considering all current emission-reduction commitments and policies. This includes Canada’s commitment to reducing emissions by 30% by 2030. Both higher temperatures and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events will undeniably have great consequences on agricultural production. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the projected changes in both temperature and precipitation will contribute to a significant increase in food prices by 2050 and as expected, lead to higher poverty and food insecurity levels. While current projections don’t paint the most positive picture, mitigation options do exist!

A Green Recovery from COVID-19

Climate-smart agriculture can sustainably increase food security and income levels while adapting and building resilience to climate change. Research by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations shows that “high-input, resource-intensive farming systems, which have caused massive deforestation, water scarcities, soil depletion and high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, cannot deliver sustainable food and agricultural production.”

Instead, many local and national organizations, including FarmFolk CityFolk and Farmers for Climate Solutions, call for climate-friendly farming techniques to minimize agricultural emissions and increase the resilience of our food supply. They emphasize the need to prioritize climate resilience in agriculture as part of the COVID-19 recovery. By building resilient, ecological local food systems and supporting farmers to adopt low-emission, high-resilience approaches, we also provide ecological goods and services that benefit all Canadians.

The National Advisory Council on Poverty also shares five recommendations to maintain progress on poverty reduction efforts. Since poverty directly impacts an individual’s ability to acquire adequate, nutritious food, the solutions and recommendations for both issues are one and the same. These include:

Focus additional investments on areas where progress is falling behind—food security, housing and homelessness, literacy and the poverty gap;

Support Indigenous leaders and collaborate with Indigenous nations to develop a range of poverty reduction strategies specific to their communities;

Improve population-based surveys by asking inclusive questions and providing inclusive response options to allow for purposeful disaggregation of data;

Review, develop and implement all strategies, policies, and programs with an equity lens; and

Collaborate with provinces and territories to strengthen existing strategies, programs and policies and develop a streamlined, low barrier system.

Conclusion

The scale and scope of issues like poverty and food insecurity are well beyond the ability of any one organization to solve. It’s clear that addressing food insecurity, through the eradication of poverty, requires a comprehensive approach that tackles the issues in an equitable and environmentally sustainable way. An integrated strategy is also vital to addressing poverty in all its dimensions. We need policies geared towards a more equitable distribution of wealth as well as the empowerment of those living in poverty through their participation in all parts of social, political, and economic life, including the design and implementation of such policies.